If what we do with our time is a reflection of our personal anxieties, science journalists have a deep and persistent fear of their own deaths. Become a bioluddite.

You can maybe see this in the never-ending coverage of Bryan Johnson, the life extension millionaire obsessive who tracks the strength-over-time of his erections, takes dozens of pills per day (you can of course buy these pills from him), and never seems more than a few weeks between 10,000 word features written about him. Johnson, and a handful of other tech-adjacent people are part of a growing cadre of life extensionists, people who are actively searching for ways to extend the natural lifespan of humans, using whatever unproven and/or technically improbable platform they can get their hands on.

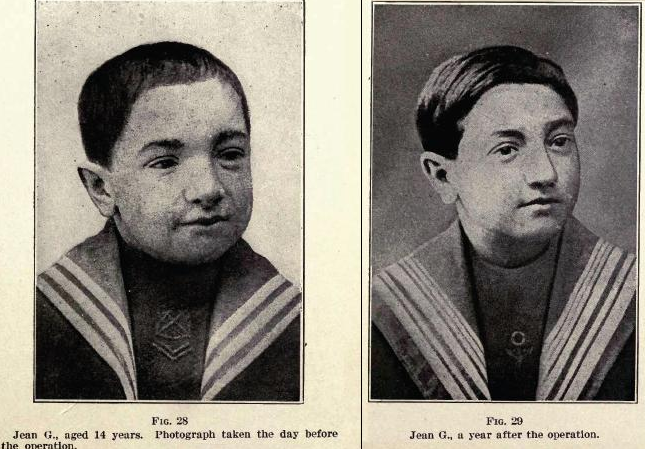

This interest/obsession, has existed for centuries, and while it has changed exact tactics slightly the tactics remain the same. There is some fountain-of-youth-type substance or personal practice. If someone takes that substance or adds a little wellness habit to their daily routine, they’ll live longer. It can be something that modern wellness bloggers swear by, like sunning your perineum. A cadre of 19th century European physicians had their own fixations. One, Arnold Lorand, was obsessed with the thyroid and thought that eating animal glands could stave off senility. One, Serge Voronoff thought that the sex organs were the key to “rejuvenation” and elongating life. He perfected a technique where he grafted ape testicular tissue (and sometimes ovaries) into a human’s scrotum. He reported doing this 475 times in the 1930 calendar year (that’s hilarious but Voronoff was still, somehow, a serious scientist who was instrumental in the invention of hormone replacement therapy). Lorand also thought that a potential route to long life was simply being a poor peasant:

If we were asked for the best means of living to be 100 years old we would say: become a peasant or a pauper and be received into an English work-house… They have no anxieties about getting their daily bread, and oftentimes are fed better than they would have been in their homes, although only the minimum amount of hygienic food is given… Workhouse inmates lead a very regular and frugal life, rising in the small hours of the morning and retiring to bed early in the evening. Thus, in winter time, they can never contract pneumonia by coming home late from the overheated theatre, concert, or clubhouse. They also need not worry about their fortunes, for they have none.

The commonality that Johnson has with Lorand and Voronoff and a million others is that they were all wrong. It’s always something. For Johnson it’s supplements with coenzyme Q and vitamin B, for Lorand it was eating thyroid glands, for Voronoff it was stapling monkey testicles to your own sack. They all had something to provide to people, something to sell even, but not one person’s life was extended by a day through that work.

I simply do not think that this is ever going to work. I do not even believe that the idea of not just preventing disease but prolonging life—not just extending a healthy lifespan (a “healthspan”) but going beyond that—is a good thing. It appears to be both scientifically impossible but also morally wrong.

As I often do when I do not know about something, I look at the scientific literature. There is, for instance, the decades-worth of research into pausing and then restarting life: crytobiology. Have the researchers who more actively tried to stop and start life's clock learned anything about the nature of life?

We can go crypto by drying, freezing, or otherwise slowing down an organism’s metabolism, something easily achievable with bacteria, yeast, and some kinds of worms. But as far back as 1968, scientists realized there was a catch, even when it comes to drying out some flies to see if they could be brought back to life:

When an organism is in a cryptobiotic state, the changes that normally make death more likely with the passage of time do not occur. These changes only begin again when activity is restored, that is, when the organism is changed from a purely morphological entity into a physiological one. When we know how to bring a plant or an animal into a state of cryptobiosis, we can increase its life-span enormously as measured by a calendar but we can in no way stop the process of ageing during the periods when it is not in cryptobiosis. Thus, although the lifespan is greatly increased, the total duration of its active life is in no way increased.

(emphasis mine)

Radical life extension brings an odd set of values to how to weigh human life. I really want to emphasize before I keep writing that I do not hate humans or want them to die except for a few choice enemies. I probably cannot convince anyone, even myself, to not value human life at least a little bit more than any other forms of life.

But I can convince myself that it values human society too much, valuing it over any other form of ecology. Radically extending our lives is a way to extend what our lives look like, and how they shape the world. Looking out my window at cars passing by, knowing how searching for gas to burn, and then burning it, has warped the climate, how the US has shaped human lives around the needs of cars and businesses over the individual person, it is hard for me to cheerlead a technological effort to keep all this going just the way it is. Every summer I check the air quality index with the same regularity that I check the temperature. Here in Minneapolis, on June 3rd we had the worst air quality ever recorded in the city, because of more than a two hundred fires burning in Canada dumping smoke into Minnesota.

It’s difficult to live in this world and see a wealthy man selling the idea of living longer as anything but another way to take more from the world. Focusing on extending one’s own life becomes so deeply selfish, another way to funnel money into the individual instead of spreading it to our neighbors. There must be some space in the scientific world to say enough is enough, that pushing and pushing forever on is not only a simple bad idea but totally counterproductive. Radical life extension seems like another way for us to shovel even more of what the planet produces into our own corner, as if all our current problems are not the result of stupendous greed and over-consumption.

Then maybe this is me coming out as a bioluddite (a phrase I did not invent). The original Luddites weren’t opposed to new inventions, they were opposed to new inventions actually making life worse. The same principles apply here—the search for a “cure” for aging or a molecule that can extend life has been nothing but a wild goose chase at best or a con trying to separate people from their money, as long as it’s existed.

Frankly I’m tired of all this. In the 19th century lifespans started to radically expand, not through supplements but in much more prosaic ways like improved housing, nutrition, and hygiene, along with combatting infectious diseases. The great miracle of the past century of research in biology has been the reveal that of just how complicated biology is. Bodies are not modular robots that can be refurbished with the right part, and the body’s biochemistry can’t be fixed with a magic bullet (to see why, take a look at this map of one part of the human body’s metabolism). Our own mortality is a primal source of fear and therefore a terrific wellspring of money for capitalism to source from. Bryan Johnson, a man who made his millions in e-commerce, does not know where the fountain of youth is, no matter what he says. It doesn’t exist.