If you ask Jack Lohmann why he wrote a book about phosphorus — an element as vital to life as carbon, oxygen, and nitrogen — he’ll first tell you about death. Growing up in Virginia, Lohmann learned about the periodic table’s 15th element as a pollutant in the Chesapeake Bay. Agricultural runoff of phosphorus fertilizers sparked feeding frenzies for algae, which would then bloom into “dead zones” where they suffocate all other life.

“I've always been really terrified of death,” Lohmann told me in his distinctive tone — a gentle sort of measured whimsy.

About eight years ago, Lohmann began a thesis project on human migration which took him to Melilla, a Spanish enclave poking out of Morocco’s northern coast, and Nauru, a tiny island housing an Australian immigration detention center. He quickly learned that both Nauru and Morocco were global epicenters of phosphate mines. The story of these life-giving deposits formed by decaying organisms intertwined with stories of humankind’s lofty ambitions and hidden abuses.

Phosphate mining that once made Nauru wealthy has stripped large swathes of the island barren and uninhabitable. Refugee camps were built inside abandoned phosphate mines. Human rights abuse allegations followed. “The island was hollowed out,” Lohmann said. “It felt to me really symbolically important that this island was mined for this substance that's so closely associated with life,” Lohmann said.

I recently spoke with Lohmann about his new book, White Light, which author Elizabeth Kolbert calls “lyrical and exacting, clear-sighted and deeply informed.” On every page, Lohmann chooses beautiful words and scenes to build this narrative. Here is Lohmann, speaking with Sequencer about that love of words and why everyone should care about phosphorus.

How did your preoccupation with death frame your early interest in phosphorus?

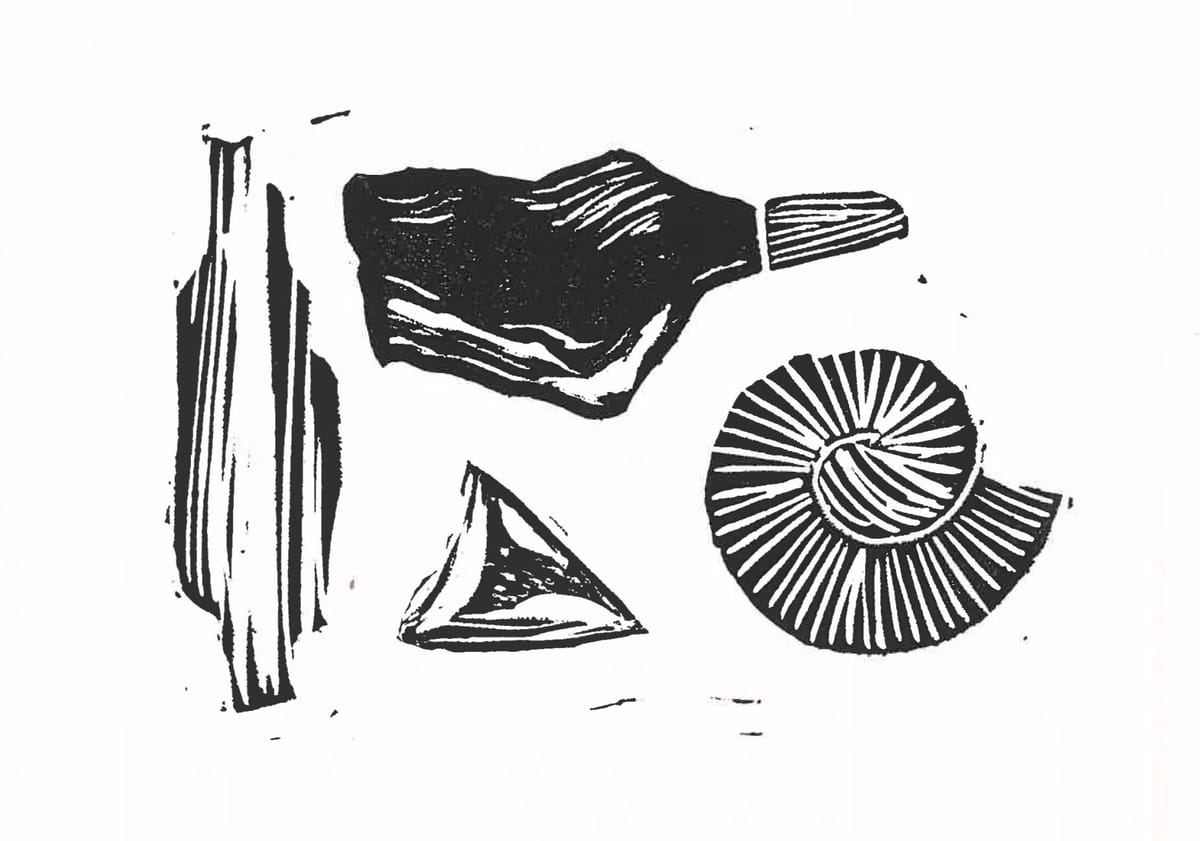

From a young age, I gardened with my grandmother, and I remember going into her tool shed and picking up bags of fertilizers that were made from animal parts, dried blood for nitrogen, ground up bones for phosphorus. At the time, I didn't place much importance on it, although I was fascinated by the objects themselves.

The fact that I could pick up these crushed bones that were used as a phosphate fertilizer — that carries over into the language. I'm a very tactile person. I like the way things feel. I think that comes across in the writing of this book.

Did you feel awe at any point while writing the book?

All the time. Every page was filled with awe. I loved talking to people and listening to people. Everybody uses language in a different way. Writing a book like this, I also talk to so many different kinds of people, different kinds of specialists. Maybe their language is different or they use different jargon. I loved getting used to the way chemists talk or the way biologists speak, or spending time in refugee camps and hearing the kind of humor that's pervasive there. Whatever it was and whoever I was speaking to, I tried to convey that on the page. I tried to carry people's voices across. A lot of the editing process of this book was my editor, telling me I had to cut all kinds of long, extended quotes of people — I wanted to include so much. I thought it was, it was just wonderful hearing the way people spoke.

[Note: What Lohmann just said resonated a lot with me, so I'm including the next answer as audio.]

Is there a tactile memory from the book that stands out the most?

You write “A straight line runs through the history of Nauru from the rise of phosphate to the loss of knowledge, from the loss of knowledge to the end of hope.” Why is this an important observation?

When we lose our connection to the land, we lose a lot of our culture and our will to live. In Nauru, specifically, phosphate mining took over the national economy. The land was removed, and the knowledge of how to live dwindled away.

There might be little pieces of Nauru in your teeth.

It's often held up as a metaphor. The entire island was strip mined — more than 80%. When the mining left, the whole economy collapsed. That's not hyperbole. It's true. And now refugees provide the economy. And when I say refugees, I mean these illegal payments made by the Australian Government to the Nauruan government to hold vulnerable people long-term against their will. It's the vast majority of the GDP of this country. When you disrupt natural cycles, it's really difficult to fill that void. It's striking to see what happened in the aftermath when people lost connection to what was around them. You lose empathy and you lose hope in that situation.

How would you explain the intertwined story of phosphorus to someone who has never thought about it?

I talk about what we eat. If you lived in Australia or New Zealand or Europe or parts of the United States during most of the 20th century, you probably ate some of Nauru’s soil. That phosphate that was removed from the island, almost 100 million tons processed into fertilizer sent around the world, used to grow food, and those little bits of phosphate that ended up in the foods that were produced are in our bodies. They form the structure of our DNA. They form our cell membranes. They are part of us. There might be little pieces of Nauru in your teeth. It's eerie to think about when we talk about mining, the goal is often to mine or to obtain something that will be used, maybe as an energy or a building material — something to put in your phone, something to burn for fuel. Phosphorus is different because we're eating it. It's going into our bodies. It's forming our bodies.

If you then read in a newspaper about human rights abuses happening in Nauru, you're implicated against your will. You're implicated in this international human rights story. Your body is a part of that story.

When I talk to people about phosphorus, I talk about it not as an element or an idea, but as something that's a part of our lives, that makes up who we are, and that has really, really complicated resonances around the world.

I'm a very tactile person. I like the way things feel. I think that comes across in the writing of this book.

How did the story evolve for you compared to how it appeared in 2018?

When people tell the story of phosphorus, it usually is left off at dead zones. We talk about mining, we talk about fertilizer, overuse of fertilizer, pollution into lakes and rivers, and often the story ends there. With this book, I tried to expand the timeline of the story very far into the past and also very far into the future. I give a lot of time to early farmers, to old phosphorus cycling, the ways in which the phosphorus cycle has changed throughout the history of humanity and throughout the history of the world.

When you disrupt natural cycles, it's really difficult to fill that void

You open the book with a scene of a nutrient-rich whale carcass sinking to the ocean floor. In what ways does a “whale fall” exemplify the book?

Sometimes there's a lot of available phosphorus, sometimes there's very little, but there's always the same amount of everything on the earth. It's like an island. A world and an island are both a bit like a whale fall — a place that is teeming with life and also really, really isolated. Whale falls exist in the dark. Plants can't grow because there's no sunlight. It's a different kind of ecosystem where you see all of this life congregating around this one pocket of available nutrition. I wanted to open the book with that, because that's the theme of the book: feasting on death. It's a different way of thinking about the world.

Did working on this book change your fear of death?

I wish it had. I'm still just as concerned. But I understand my place in the world better. The role that I will play after I die is not so different from the role that I'm playing now. Earth and life have co-evolved throughout this time through phosphorus. Phosphate rock is an indicator of life. When we return phosphate to the ground in the form of death and waste and vegetable clippings, we are participating in that cycle. We're making that connection real, and for me, at least, that's comforting.