To say you “like chocolate” means almost nothing. There are people for whom chocolate means the rich soup of microwaved Ben & Jerry’s Phish Food; some gravitate to the syrupy bite of Hershey’s and others refuse to call Hershey’s “real” chocolate; there are the Lindt Lovers, Ferrero Rocher Freaks, and organic-bean-to-bar-fair-trade fans and stans. And then there’s Seamus Blackley, a physicist by training who didn’t think much about chocolate until he and mechanical engineer Asher Sefami began growing cacao trees in a secret lab just east of Los Angeles.

When I learned on Bluesky that Blackley and Sefami were operating just a few miles away from my home, I called them up, and they invited me to check out their DIY setup. Shortly upon entering the lab, Blackley’s team greeted me with a latte and an NDA. (The cacao project is just a hobby that shares a roof with their more serious venture for the time being.)

About six years ago, the pair decided on chocolate after a range of cultivated exploits. Sefami, who successfully grew weed in his home, ordered cacao plant clippings; Blackley is a fermentation enthusiast who houses at least 17 sleepy yeasts in his home freezer. Both welcomed the challenge to grow a snack.

Despite being relatively close to the Mesoamerican birthplace of chocolate, Blackley and Sefami quickly realized they’d underestimated the difficulties of making even a gram of passable chocolate. The chemistry and physics weren’t bogging them down — tempering chocolate around 90°F to get the snap from uniform crystals is almost banal. It’s the microbiology of chocolate that’s uncharted territory. Their scramble to grow a treat landed them in unexpectedly fertile ground to experiment with yeasts and bacteria.

Chocolate comes from hot rainforests in equatorial regions. It needs heat, humidity, and a just-right trickle of nutrients. That’s not Los Angeles. That’s not most of the world. Companies usually import roasted cacao beans or (gasp) bulk chocolate. But even unroasted beans are alien to what makes chocolate chocolate. The treat process really starts with the whole fruit: colorful, burrito-sized oval pods that hang beneath large green leaves. Crack open the pod’s bumpy shell and you’ll find dozens of fingertip-length beans drowning in white fleshy goo.

This is the good stuff. The beans and goo, known as pulp, must be fermented and dried for a week before you catch a whiff of something that even resembling chocolate. (Raw pulp tastes light and fruity. It makes delicious juice.)

Blackley and Sefami sought to grow this fruit from scratch in their nondescript San Gabriel warehouse and ferment delicious chocolate with as much scientific control as they could muster.

Fermentation, Blackley will tell you, is the most important step to developing flavor in good chocolate. Native yeast and bacterial species devour sugars and other molecules inside the cacao fruit’s white pulp. They produce alcohol, heat, gases, acids — essentially, a wave of chemical change that seeps into the bean itself. Enzymes mince proteins into fragrant aromatics. Polyphenols deteriorate then fuse into bitter tannins. Alcohol and acid molecules collide, gifting drips of sweet esters. It’s a similar chaos to the one that bestows complex flavors to cheese, wine, and soy sauce. Again, the good stuff.

It took two years for Sefami to notice flowers on the six-foot cacao tree growing in the metal barrel. “Hell yeah, chocolate! We're gonna get chocolate,” Sefami recalled saying prematurely. Flowers forerun fruit, but cacao can’t self-pollinate. The trees need pollen from a genetically different cacao plant to create fruity offspring. Sefami ordered more clippings on eBay and waited two years for those to flower. And since you (unsurprisingly) can’t import the mosquito-like cacao pollinators known as chocolate midges into California, Sefami learned to pollinate each flower by hand.

"We do these things not because they are easy, but because we thought they were going to be easy." The Programmers Credo

Eventually, he and Blackley got their first pod and the experimentation began. “We got this fruit and were like ‘Shit. What do we do next?’” Blackley said. “We were in R&D mode,” Sefami added, “How do you make chocolate from a pod? It’s not trivial.” They cracked open the homegrown pods and began fermenting.

Chocolate growers ferment their fruit in a few traditional ways. Some cover "heaps" of pulp-covered beans in banana leaves. Others use wooden boxes that descend in series for different stages of fermentation. These traditions work wonders. Chocolate makers excel at what they’re doing. But microbiologists know surprisingly little about the biochemical happenings within cacao's bubbling fermentation. In 1998, Brazilian researcher Rosane Schwan experimentally developed a “starter culture” of yeast and bacteria for reliably fermenting cacao. Later, Schwan reported speeding up fermentation from seven to three days with an experimental starter culture, and observed the effects of changing cacao varieties and microbes. A 2021 case study described ambient temperature and fermentation pH as key to quality based on chocolate from three locations in Colombia.

Blackley wanted to improve chocolate flavors with experimental skills he'd refined in past food projects. Five years ago, the former videogame designer revived ancient bread recipes with 4000-year-old yeast isolated from Egyptian ceramics. (Blackley is known as the "father of the Xbox.") His home affords him control with fermenters, a thermal camera, a microscope, UV lights and autoclave to sterilize, and a lab-grade freezer set to minus 80 to preserve microbial strains. Others might call it a chemistry lab; “This is kitchen equipment for me,” he said.

The food is so exceptionally far removed from the fruit that evolution hasn’t encoded any obvious cues for the best chocolate.

This set the stage for Sefami and Blackley to merge the art, craft, and science. Blackley constantly tracks temperature and humidity, examines fluids under his microscope, and carefully decides when to halt fermentation — after the temperature plummets from acetobacter but before fungi take over. "You get hints of chocolate, and also feet," Blackley told me.

Chocolate's essence comes to the fore after drying and roasting the fermented beans. “There's a point in the roasting where your house just smells like brownies, and you're like ‘what the fuck has happened here?’” Blackley said. They milled, tempered, and tasted the first bar in 2023. It shocked them. “It's ruined us and our families and everybody who has tried it.”

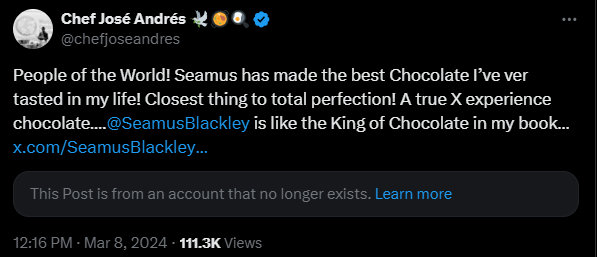

Among those who have tried it is famous chef José Andrés, who connected with Blackley during the Egyptian bread project. Blackley brought Andrés a sample of their third batch. “He ate it right in front of me,” Blackley recalled. “I was massively nervous.” Andrés loved it, and later tweeted “Seamus has made the best chocolate I’ve ever tasted in my life!”

When I visited the lab, Blackley and Sefami had recently finished another batch. They’re very much still tinkering. The food is so exceptionally far removed from the fruit that evolution hasn’t encoded any obvious cues for the best chocolate. That makes cracking the optimal chocolate an engineering problem. What’s the best moment to pick the fruit, considering how ripeness changes sugar levels and therefore fermentation? What is the best pH for each fermentation step? How do different varieties and their hybrids (they now have several) affect flavor and conditions? Blackley inoculated a recent batch with a rare yeast that contributed a distinctive lily odor.

For all of this talk of control, I wondered whether Blackley and Sefami risked being overbearing stewards of their microbes. Fermentation is nature’s delicious serendipity; you cede control of flavor to whichever microorganisms out-eat their counterparts, and you sometimes reap the benefits. One yeast might thrive if temperature creeps up; another might indulge when humidity dips. But the two assured me that controlling organisms with every tool available doesn’t rob their product of a microbial soul. They insist the opposite. “You want to surrender,” Blackley said, so your creation can soar on intuition alone.

“Art isn't wandering randomly in the dark,” he added. “We figure this stuff out so that we can let the natural process happen in a way that really maximizes how beautiful it can get.”

A week later, I returned to taste the chocolate from their seventh fermentation. Blackley handed me a baggie with two small cubes — about 25 grams total, staring at me, daring me to “ruin” my taste for other chocolate. A fragrance danced up my nose the moment I bit down. I can’t declare it the best I’ve ever had (my personal favorite is subjective), but it did take considerable effort not to devour in full on the spot. This chocolate is special. Blackley and Sefami's microbiological guardrails make it consistent. It’s not beholden to weather’s effects on “terroir” or fermentation or drying steps. And they freaking grew it. Here. In a barrel. Southern California! Chocolate! Whether this means something to you or not, I like it.