About five months ago, I set out on a humble mission in my neighborhood. Though I have a good number of friends sprinkled across the sprawl of Los Angeles, I’d been wanting to extend more hyper-local roots. Community is notoriously hard to come by here, so one morning, I hatched a plan — frankly the first plan that came to mind — to become A RegularTM somewhere around the block.

I wanted a sense of home; I wanted to exchange faces and names. More than that, I wanted to be a face and a name.

In hindsight, the mission was pretty true to form for me: an unimpressive goal rendered lofty by poor strategy and clumsy execution. I live beside a ludicrously trendy coffee shop, the type of place that sees many, many faces and names all day everyday. Faces and names accessorized with distinctive hairstyles and thin-line tattoos. Faces and names more recognizable than mine, flung quickly at busy baristas who ping-pong their attention between drink orders and a line that famously stretches 40 feet out the door.

But I like their matcha. I like their afternoon light. I like the buzz of their patrons. So, one Sunday in May, I walked over, ordered my usual-to-be (iced oat matcha: $8 incl. tip), found a seat, and journaled while nursing my soft green drink.

Over the next seven days, this became a new ritual. Some days I chatted up strangers. Some days were unusually packed. I never went at the same time, and I rarely saw the same people. But I began to wonder: was I really not seeing the same people? And how could I be sure? This took me down a facial memory rabbit hole. I can recognize the baristas who I always see in the same 20-square-foot space behind the counter. But would I recognize a guy pretending to read Joan Didion today if he showed up without the same performatively dog-eared copy of Slouching Towards Bethlehem weeks later? Would I recognize the Parisian girl who kindly renovated my French slang were I to run into her on the street?

As I summoned mental images of various café folk, I realized: I couldn't picture every face. Even faces that I knew I'd recognize were difficult to recall.

I’d hit upon a fundamental quirk of human memory. Remembering is not a monolith: Recall and recognition are two very different challenges for your brain.

And conjuring an image is the trickier of the two. It requires both a memory and an ability to neurologically paint that memory in front of your mind's eye. Though most people can do this more easily with photographs seen repeatedly, attempting to imagine a recent face can feel like twisting the key into an ignition that just won't budge.

Remembering is not a monolith: Recall and recognition are two very different challenges for your brain.

“Visualizing faces can be oddly difficult, even faces of people you're very close to at times,” said Adam Zeman, a neurologist who studies memory and imagery at the universities of Edinburgh and Exeter.

But why? Facial recollection plays a crucial role not just in our modern-day lives, but in our evolutionary history as a highly social primate, too. Neuroscientists have progressed our understanding thanks to fancy imaging equipment and naturalistic memory testing. They’ve identified some cues that help our brains recall faces. We also know that the human brain comes equipped with face-specific machinery and neuronal highways that beam signals correlated to how we process emotions, vision, and so on. More research is revealing a litany of open questions about facial memory, and the answers trickling in can reward us with a new appreciation of our brains — charmingly imperfect and unexpectedly diverse.

Total Recall

It's hard to pinpoint where a memory lives in your mind. Our memories are less like sheets of paper stored in a filing cabinet, and more like flashes of electricity, lighting distinct webs of interconnected brain cells. Each flash is a (somewhat) repeatable pattern that conjures thought. For example, the smell of cinnamon dances up your nostrils and, FLASH!, a memory of your aunt’s apple pie packed with baking spices awakens in your mind.

A c-shaped nub of gray matter known as the hippocampus is generally regarded as a “memory center” that harmonizes memory signals that run all over the brain. So individual memories span the brain like Christmas lights on a sweeping pine. A basketball player’s "muscle memory" of a jump shot flickers among the movement-savvy connections in the basal ganglia; trauma imprints upon the amygdala; songs etch along the auditory cortex. (Of course, these categorizations are not mutually exclusive: one memory can invoke all three areas and more.) To remember a face, your hippocampus works with the fusiform face area, among other areas.

But when we talk about remembering a face as stored data, we need to ask what we're actually remembering. When we do, we already run up against the limits of our knowledge. Are faces stamped as clusters of eyes, noses, and mouths into our mental banks, or are they separated into sets of discrete parts — an especially distinctive pair of ears singled out, or a button nose, or cheeks the size of water balloons, or a sharp chin that could pop said balloons?

We do know that we tend to pay attention to certain features more than others. “Eyes are a big one,” said Stephanie Leal, a cognitive neuroscientist at UCLA. People also tend to focus on whether a face is symmetrical or unique, she added.

Leal develops tests that measure people’s facial memory. It’s a field ripe for innovation, since the standard experimental methods are imperfect. Many studies will exclude emotions or hair, but Leal believes both are important components of naturalistic faces, and by extension, tests. In 2023, she published results of an experiment that challenged participants to remember faces amid “interference.” Participants were shown faces that they were later asked to recognize in a more challenging context. “Maybe their hair looks different, or they're wearing glasses. Or we show them pictures of [different] people that look very similar,” Leal said. It was a more rigorous test that was difficult for all age groups, especially older people.

In general, older adults report struggling with faces and names more than young people do, but we don’t know when exactly that deterioration starts to occur. Leal wants to detect that subtle decline early. “If you catch the problem early enough,” she said, “there is a potential way to intervene.” She believes that facial memory is “plastic” in this sense. But to test that — let alone prove a reliable measure of facial memory — we need more naturalistic tests that capture the full complexity of a face.

And make no mistake: faces are extraordinarily complex. Bear with me for a few seconds of math.

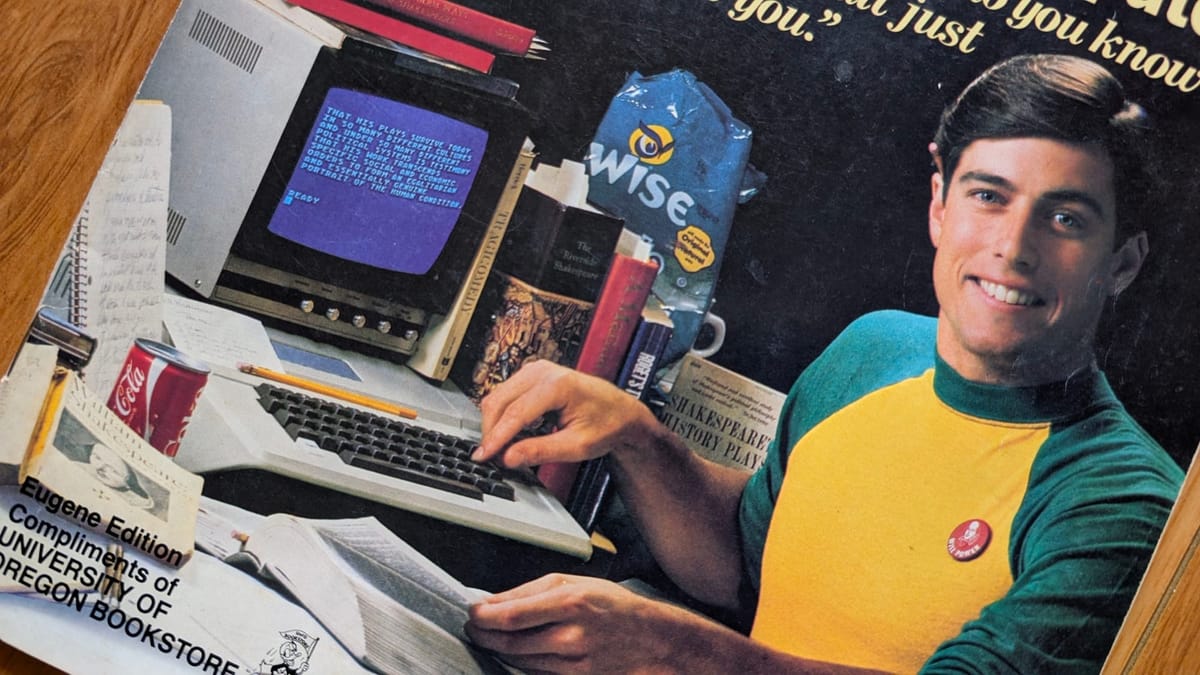

Suppose we want to estimate how many different faces we can design by combining a set of facial features. For the sake of this Mr. Potato Head-esque thought experiment, let’s keep things conservative by claiming there are only five different versions of each feature — only five different noses, five different eye colors, and so on. Now, let’s say we designate just 15 traits‡. How many combinations can we build? 515 = 30.5 billion.

A lot of choices go into a face. It’s speculated that we can only dream about faces we’ve already seen, rather than building new ones in our imagination.

This example is admittedly imperfect, but it illustrates how the feeling of recognizing a face can be so unmistakable. Each face leaves a complex impression on your mind. Of course, knowing that you know something is a very different beast from knowing how you know it. It might take a split second to know you’ve seen a face before, but take minutes to parse out why that face is recognizable.

Picturing a face in your imagination well enough to dissect its details must be a taxing mental challenge. And neuroscientists like Zeman have learned that this ability isn't a given. The connections wired in your brain influence your abilities compared to someone else’s, and even compared your own.

Forgetting Faces

Zeman has become quite introspective about his face recall skills since he began studying how people imagine visually. His mental imagery skills vary day-to-day, generally based on mood or energy level. “If I'm having a kind of bouncy day, I'm more likely to be able to visualize vividly than if I'm tired or feeling a bit off,” he told me.

But even a tired Zeman possesses an ability that many others lack. There are many people Zeman meets who simply can't visualize anything.

The inability to visualize, which Zeman coined “aphantasia” in 2015, affects about 1 to 3 percent of the population. The classic test asks to visualize an apple. Four degrees split the spectrum range from perfectly realistic to vague or dim; degree five means drawing a blank. People with aphantasia can recognize but not reconjure. So they know the features of an apple but can’t see those features mentally.

Erika Slepian, a 28-year-old with aphantasia, only realized that she had the condition this past year. Slepian’s therapist had asked her to imagine placing her feelings in a box. She didn’t realize how literal this assignment was until later, when she came across TikToks and articles about aphantasia. “When I saw the videos initially I was like, ‘Wait a minute, is this me?’,” Slepian told me. “I thought I was being a hypochondriac, so I started asking people what they see in their head, and it became clear that people had actual images.”

When I asked Zeman about how people with aphantasia fare with faces, he told me a recurring anecdote of their anxiety about recognition. “They say, ‘I was really scared when my child first went to school that I wouldn't recognize him or her at the school gate,’” Zeman explained. But that anxiety subsides when they see their child’s face and immediately recognize them.

Zeman believes people with aphantasia lack a kind of “extra step” that regenerates an image in their mind’s eye. The extra step is a chirping from the brain's decision and attention centers to the facial processing regions like the fusiform gyrus and inferior occipital gyrus. When you decide to visualize, you use that decision (neurologically speaking) to activate visual areas. A cascade of electrical signals flow from the prefrontal cortex (handling complex thinking and attention) and the parietal lobe (processing sensory and spatial info) to memory and sensory counterparts.

“People have described image regeneration as vision in reverse,” Zeman said. “It's not quite as simple as that. There's probably always some to and fro between expectation and perception, but that's a rough approximation.”

People with aphantasia may have some difference in their brain connectivity that makes that reverse step more difficult, even if it isn’t as simple as saying that they can’t see in reverse. Aphantasia research has backed up this idea. When participants were studied inside functional MRI, researchers have observed either stronger or weaker parietal lobe activity depending on their visualization abilities. Low visualization ability correlated with weaker parietal lobe activity.

“People have described image regeneration as vision in reverse,” Zeman said. “It's not quite as simple as that."

Neural Diversity

Neurologists don’t know exactly what causes aphantasia, but genetics likely has some influence on how your brain wires up. Aphantasia is 10 times more likely to occur to an immediate family member of someone with aphantasia than to a random person.

Zeman’s insights into aphantasia tells us something about how all of us reconjure faces, too. Visualization abilities span a spectrum. Sequencer reader Becca Krall’s mental imagery is less vivid than her girlfriend’s, but Krall is far better at recognizing faces. “My partner and I seem to occupy complete opposite ends of the spectrum in this aspect. I have a really good memory for faces and hers is pretty dogshit,” Krall wrote me in an email. “I'm convinced I could go buy a sweatshirt and sunglasses she's never seen and walk right by her on the street without her noticing.”

We might marvel at someone who can draw any face from memory, but one brain’s connectivity is not inherently better than another. “There are quite a lot of good ways of connecting up brains,” Zeman said.

I’m generally quite good at both recognizing and visualizing the faces of people I’ve met. But since childhood, I remember struggling to reconjure faces of certain people within the first few weeks of knowing them. Strangely, this strikes extra hard in the early days of a romantic interest. It’s a pattern that I’ve noticed from middle school crushes through the first few weeks of every relationship of my 20s and 30s. And I’m not alone.

When I pitched an essay about facial memory on our Sequencer Slack a few months ago, my colleague Maddie echoed something similar, unprompted. “The more I know someone, the harder it is for me to picture their face. Like, I can easily picture my yoga instructor’s face, but my boyfriend’s is very difficult for whatever reason,” she wrote.

This mental block is counterintuitive, anecdotal, and it does eventually dissolve for me. But even before it dissolves, there’s always a window in which I visualize any elusive face: falling asleep. I conjure my most vivid mental images in these sleepy moments.

When I asked Zeman about my observation, he immediately sympathized from his own experience. He suspects that whatever contextual or emotional block on faces we experience lifts as our mind prepares to dream.

Also, he added, people with aphantasia can dream. “They quite often have vivid dream imagery even if they can't visualize at all during the day,” he said. “It is as if there's something inhibiting imagery which kind of releases its grip as you relax and drift off to sleep.”

Toward a better mind’s eye

Even with the advances of her 2023 study, Leal admitted that neuroscientists still don’t have a fully naturalistic measure of facial memory. She hopes to learn more about how videos jog memory of faces by capturing movements and expressions.

“The more complexity — like our real life — I think the better we're going to be able to understand how this all works,” she said.

Facial recollection plays a crucial role not just in our modern-day lives, but in our evolutionary history as a highly social primate, too.

Part of that complexity is likely a social context, as well. We strive to remember faces to engage socially. Some people may struggle to remember faces not for any neurological reason, but rather because of some social factors beyond our current understanding. “That's a huge part of cognitive neuroscience that isn't really investigated,” Leal said.

Earlier this year, a team of experimental psychologists reported the first evidence linking face recognition to semantic processing — how we process words and concepts — not just visual processes. That may help inform why some people with aphantasia are great at giving visual descriptions, despite not visualizing. The authors of the study wrote, “The ability to robustly recognise faces is crucial to our success as social beings. Yet, we still know very little about the brain mechanisms allowing some individuals to excel at face recognition.”

Zeman’s team suspects that there are different subtypes to aphantasia, and in particular, one subtype tied to facial recognition difficulties. His team also hopes to scour biobank data for genes involved in imagery.

In his personal life, Zeman continues to prod at his memory and imagery. This summer, he tried to mentally flip through the faces he sees on his jogging route two or three times per week. “The [mental images] were probably crisper than the images I would have been able to conjure of people I'm very close to and spend time with every day,” he said.

Zeman’s experience is somewhat similar to what Maddie and I both experienced — being able to picture a lesser acquaintance’s face more vividly than a closer one’s. But in thinking about it, Zeman wondered if what underlies this contradiction is that vision is a “distance” sense. We rely on sight to tell us about our distant surroundings, more so than smell or touch, for example.

“This is a kind of a metaphor,” he said, “but maybe the closer you get to people, the more difficult it is to activate that ‘distance’ sense.”

There’s no scientific conclusion to draw about faces and metaphorical distance yet. And, for what it’s worth, I don’t feel I relate to Zeman’s described experience here. The more salient takeaway I gather is the remarkable diversity of facial memory. My experience may overlap with others’, but there seems to be something special in how each of us remembers a face.

I stopped my daily visits to the coffee shop about one week into my mission. Over summer, I often went several weeks without popping in at all. But I’m no longer a stranger. Months ago, I found my first evidence of that on — surprise, surprise — a face. I noticed a patina in the gaze of one barista who saw me. It reflected something that had changed behind his eyes: an almost invisible signal no louder than the memory it leaked; a look that you’d have to try hard to imagine, but that you’d know if you saw.

First the gaze as I entered. Then a wave. Then a smile. “How are you?” he said. “Remind me your name?”

‡ The 15 facial features I used for the Mr. Potato Head Analysis

eye color, eye shape (size, separation, angle), nose shape, nose size, lips, mouth & teeth, eyebrows, head shape & size, face shape, size, structure (cheekbones, forehead, chin), hair, expression & symmetry, discerning features, skin tone, age.

Note that I omitted presenting gender and body shape. These surely factor in but I wanted to keep focus above the neck and be conservative in the estimation as possible.