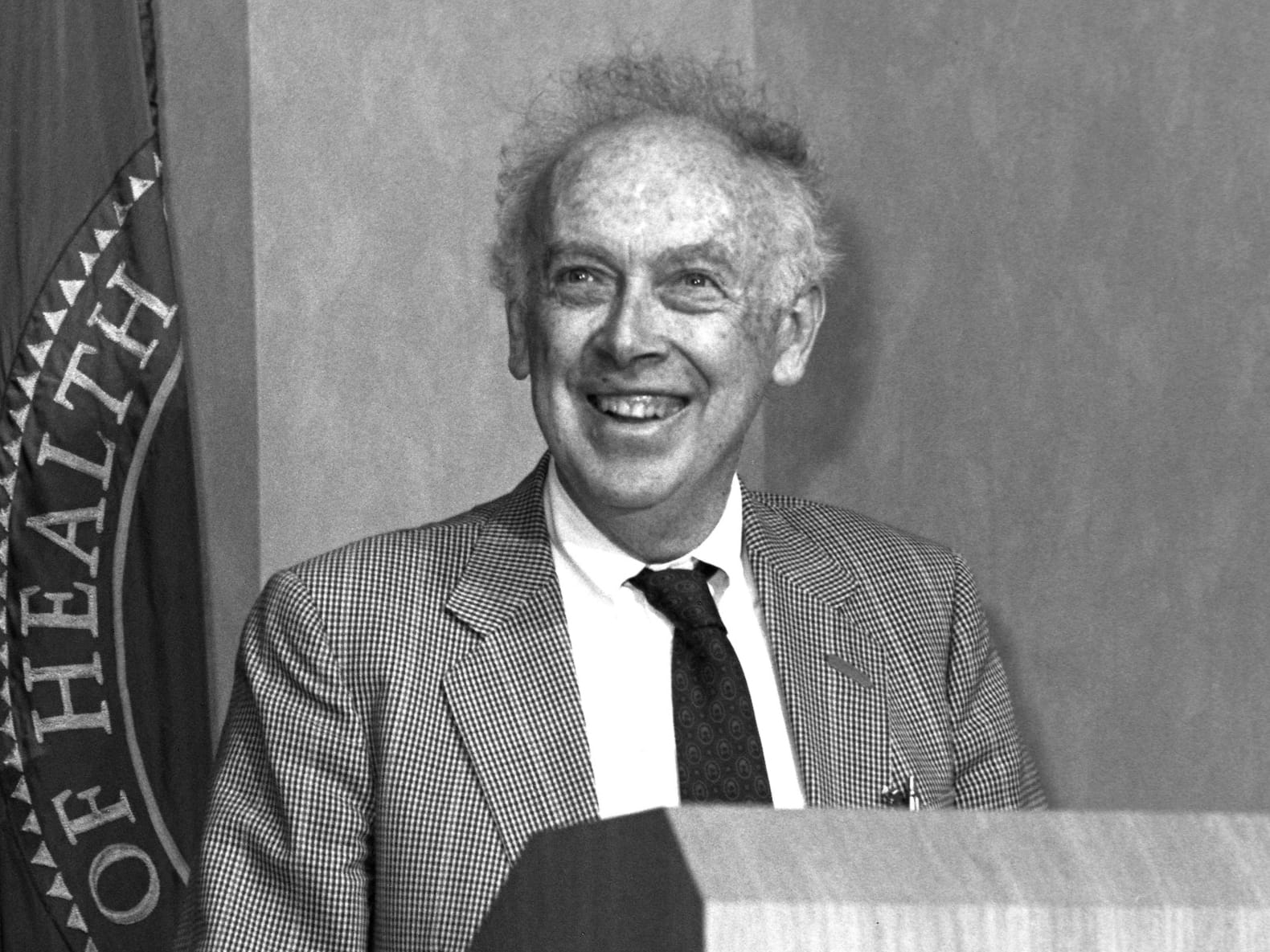

James Watson, the Nobel Prize winning biologist who, along with Francis Crick, discovered the structure of the DNA’s double helix, died last week at the ripe old age of 97. That is a long life for anyone, especially biology’s embarrassing grandfather. While he had been out of science’s eye for quite some time, it’s still considered in 2025 bad taste to dance on someone’s grave. Nevertheless I am relieved to see him gone. For many reasons.

One reason is the many vile things that Watson believed, which I’ll excerpt here in his own words (indebted to Lior Pachter for collating these):

- "all our social policies are based on the fact that [African] intelligence is the same as ours…whereas all the testing says not really"

- “Indians in [my] experience [are] servile.. because of selection under the caste system”

- “Disabled individuals are genetic losers”

That list goes on and on. Pick a form of intolerance and hatred of any stripe — misogyny, anti-Semitism, implying an evolutionary source of the sexual prowess of “Latin lovers” — and Watson had it rolling around in his head.

Alright well. Watson was a horrendous person, that much is clear. Was he at least a really brilliant scientist, without whom we never would have found out what DNA looks like? Would that level the cosmic balance?

In both Watson and his collaborator Crick’s telling of how the double helix structure of DNA was eventually determined, it was Watson who made the fundamental step of putting G bases with C bases, and T with A, in the correct orientation, in a double helix. Crick, for his part, was more modest about the discovery. He credited others — Erwin Chargaff, the biochemist who showed that G and C bases occur in equal numbers as each other, and so do T and A bases, implying some sort of relationship between them, a fundamental insight at the time.

Crick also mentioned Jerry Donahue, a chemist who corrected Watson’s misunderstanding of what chemical form DNA’s bases would take. And of course chemist Rosalind Franklin and her student Raymond Gosling, who produced the crystallography images that implied a double helix — perhaps the most important clue to what DNA looked like, especially for a roster of scientists who at one time were trying triple helices and inside-out helices.

“If Watson had been killed by a tennis ball I am reasonably sure I would not have solved the structure alone, but who would?” Crick wrote in a reminiscence.

“I solved it, I guess, because nobody else was paying full-time attention to the problem,” Watson says in Horace Freeland Judson’s account of 20th century molecular biology, The Eighth Day of Creation. That is a strange thing to say about something he was very definitely working with Crick on, not to mention two-time Nobel winner Linus Pauling, whom Watson and Crick were very conscious of racing to determine DNA’s structure.