I spend a large portion of my work day feeling confused. I start my days bewildered by advances in niches of science that I only recently learned existed. Chatting with experts usually resolves my initial confusion, but immediately after spawns more: Every question begets an answer and more questions, ad infinitum.

To me, there’s no more jolting brand of bewilderment than doing a double take on the everyday things. New discoveries may lurk in the mundane. The ubiquitous, almost cartoonish image we have in our heads of the Earth might seem like a trivial matter now, but seriously, how did we get there?

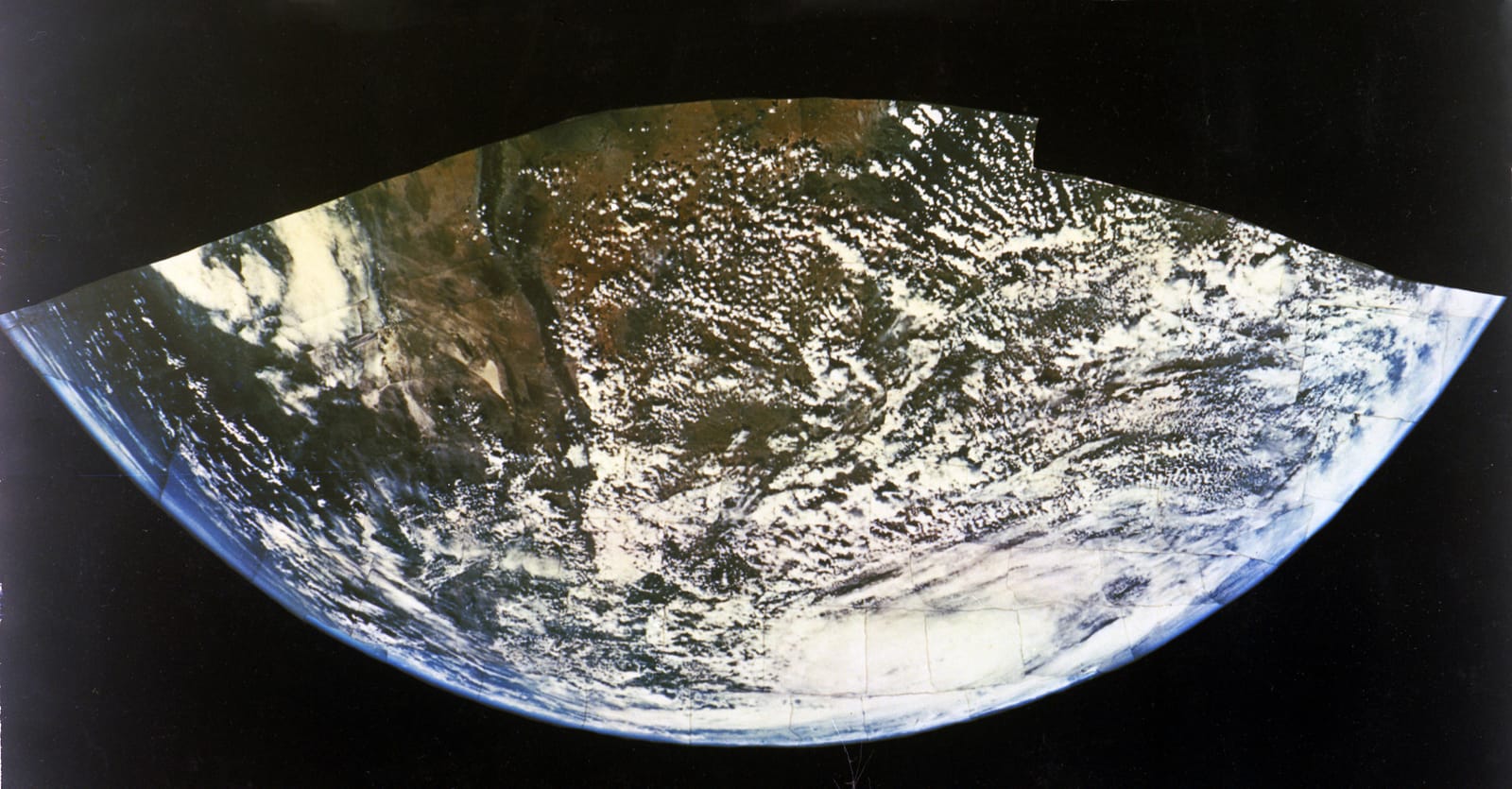

So let’s first lay out what I mean by Earth’s appearance. How did we know how to draw Earth until we sent cameras and people into space to snap some pictures? Sure, we know that land is greenish, oceans are blueish, and that mapmakers have spent millenia tracing the contours of continents, but these details tell us about Earth’s appearance in theory more than in reality. Think of it this way: I know the color of my hair and skin, as well as the shape of my head and mouth, yet I still study the bathroom mirror in the morning to see who or what I’m working with that day. What about the appearance of that Earth—the “woke up like this” Earth?

Turns out this wasn’t a trivial problem; and in some ways, we kinda didn’t know what Earth actually looked like until we saw it from space.

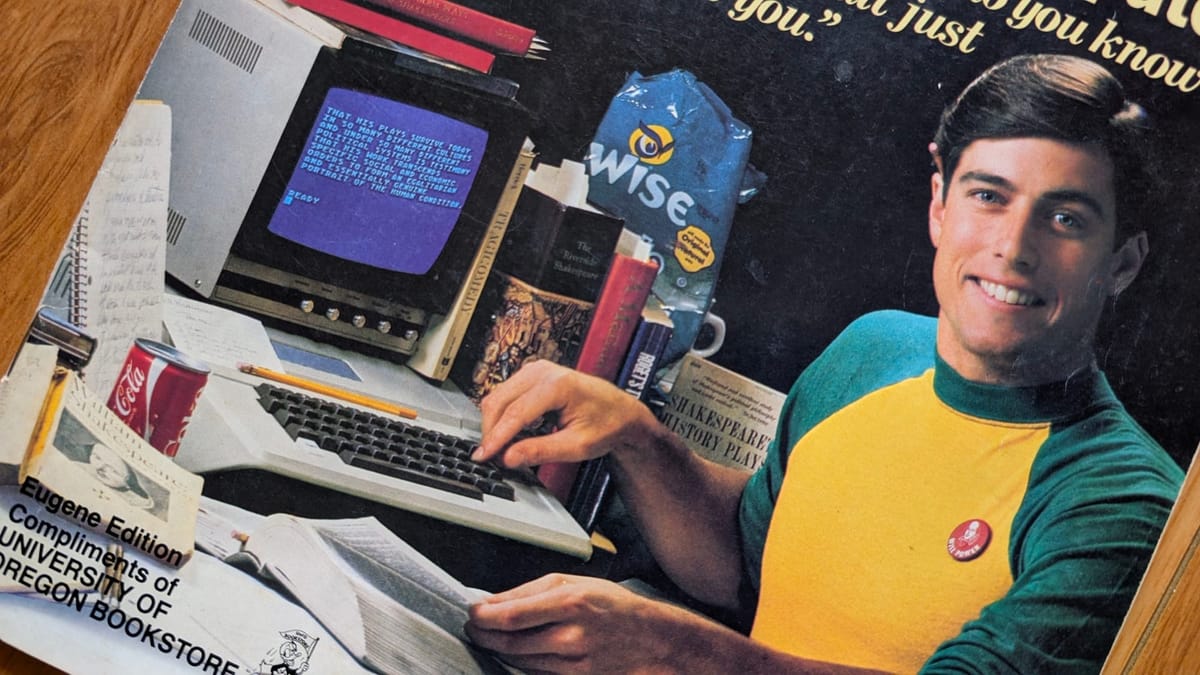

Let’s time-hop a little. Notable depictions of Earth from the century prior to space travel offered a context to imagine what Earth would look like to an otherworldly observer. In 1834, British geologist Henry De la Beche etched Earth floating in space, and depicted familiar continents overlaid by flows of currents or clouds. His depiction of continents reflected the work of cartographers before him, and De la Beche’s image placed a scientifically accurate image of Earth within a cosmic neighborhood. In the late 1800s and early 1900s, French astronomer Camille Flammarion imagined Earth viewed from the moon and from Mercury—our homeworld a mere speck from these distant vantage points, as if to simultaneously suggest that we’re cosmically insignificant and perhaps not alone. Decades later, in 1956, the book The Exploration of Mars featured an illustration by Chesley Bonestell that filled in colors of Earth’s grasslands and deserts, with various blues in the ocean, and shaggy clouds that neatly streaked the globe.