This essay was produced through Sequencer’s Storytelling Mentorship Program. Your support through donations and subscriptions helps early-career scientists and creatives tell stories you won't find elsewhere.

If you can spare a few bucks, consider enabling us to continue this work with a one-time donation or regular subscription for as little as $0. Thank you.

Imagine the scene of a pregnant mother giving birth. Chances are, you are visualizing a woman lying back, legs spread, and pushing hard to bring the newborn into the world. But that’s neither the only way for a woman to deliver a baby, nor necessarily the most comfortable.

Media is partly to blame for perpetuating this on-the-back-only myth. In a study, titled “How to Give Birth – According to Hollywood,” lying on the back is the dominant birthing position in films recommended for pregnant women across multiple search lists. Among the top five mainstream films on the list, only one of eight birth scenes showed a mother delivering not lying back. And in that lone scene where a woman gives birth in a bear-crawl position, the film’s characters find her to be “crazy” and “disgusting.”

It is physiologically possible for women to deliver standing, sitting, squatting, kneeling, or on all-fours. More importantly, many women aren’t aware that they have options — and should be given the power to choose.

Failure otherwise could result in consequences for mother’s and the baby’s health, not to mention lasting trauma. There is no evidence that shows that lying back is the safest position to give birth in; it’s simply the most prescribed. In the U.S., 70 percent of women delivering a baby vaginally do so lying back. This occurs despite the fact that the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommends that pregnant people be allowed to choose a comfortable position for giving birth.

“It is very difficult for women to advocate for themselves when there is a hierarchy in the labor and delivery ward,” says Amber Winick, co-author of the book Designing Motherhood: Things that Make and Break Our Births. The hierarchy has places mothers on a lower rung than the doctor.

Women lying down as a default delivery option provides doctors with easy access to the vagina and the womb. While this is important for doctors to be able to intervene should the need arise, not informing women what their options are robs them of agency.

“While the central tenet of midwifery practice was to meet women where they are, the controlled environment of a hospital meant access to the vagina for a doctor’s convenience.”

Birthing through the centuries

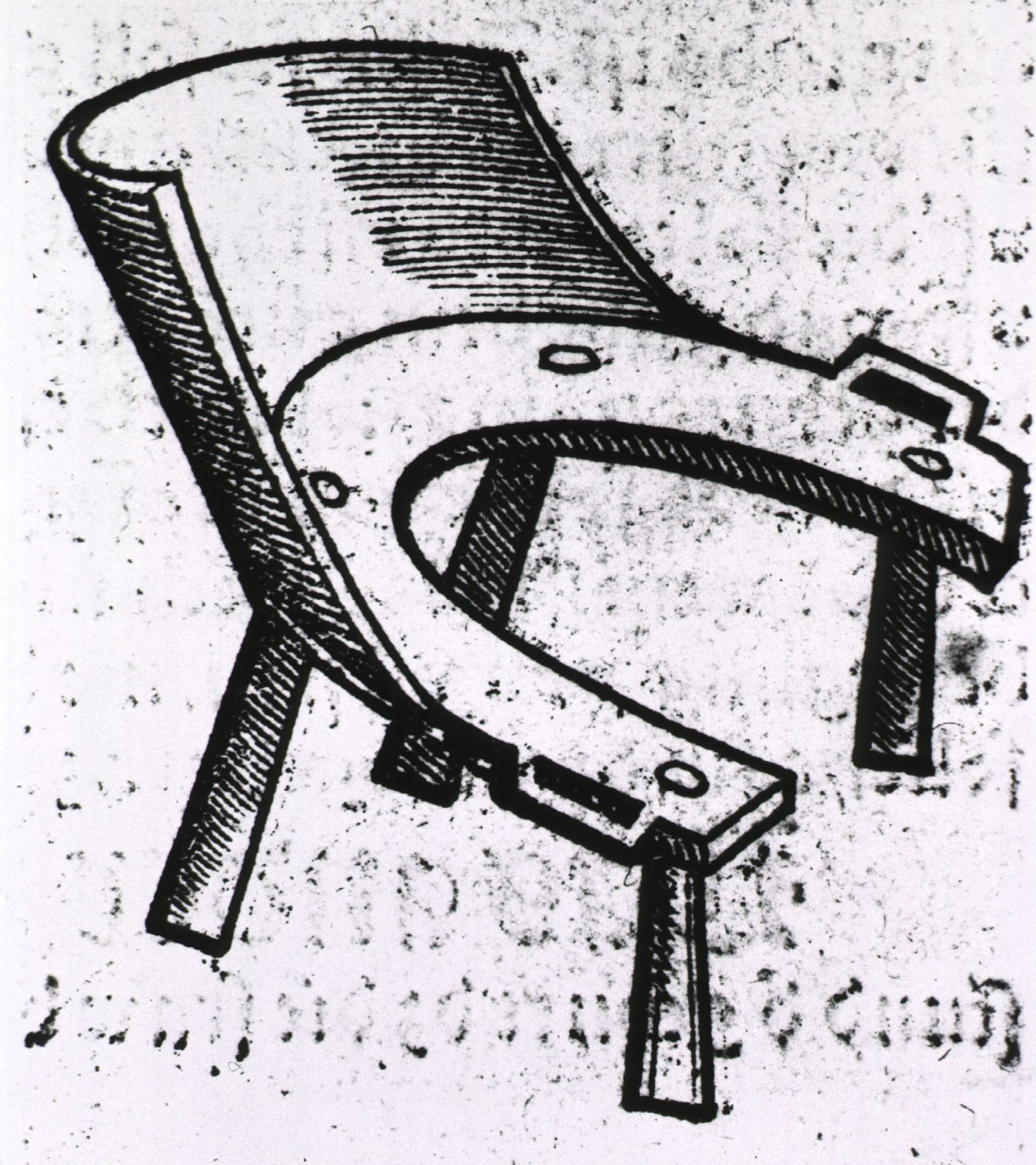

It wasn’t always this way. Women have been giving birth in upright positions for millennia with guidance from other women who were usually far more experienced, known as midwives. For example, giving birth while on a birth chair or stool, a piece of furniture resembling a toilet for its hole for the newborn to drop, dates back to 2000 B.C. A wall carving of Cleopatra at the Temple of Esneh in Egypt (around 70 B.C.) depicts her kneeling among five women and giving birth. Wall carvings of Indian goddesses from the 5th century shows them them squatting during childbirth, helped by other women. East African women were documented in the 19th century to give birth standing, with other women next to her and ready to catch the newborn.

It was only in the late 1500s that horizontal positions became popular when “barber-surgeons” became more involved with deliveries, especially to help with complicated pregnancies. At first, barber-surgeons cut and shaved the hair, treated wounds, and performed minor surgeries for all kinds of customers. As barber-surgeons took over childbirth, they replaced birth chairs with reclining beds, claiming that it would be more comfortable for women and help induce labor.

During the 1700s, King Louis XIV of France took perverse pleasure in watching his mistresses give birth, and he preferred his ladies lie back so he could easily observe his children tearing into this world. Some rumors, now mostly debunked, claim that his fetish popularized the reclining position for modern-day labor, but the credit actually goes to another Frenchman, François Mariceau. The physician argued that reclining positions were more comfortable and convenient, according to his 1668 book, The Diseases of Women With Child and in Child-Bed.

A century later, this European medical practice spurred the U.S. to adopt the lying back position as the standard. In 1832, an obstetric chairman at the University of Pennsylvania, William Potts Dewees, justified this enforced norm by holding the convenience of surgeons as the priority. He declared, “women should be placed so as to give the least possible hindrance to the [operations] of the [obstetrician] — this is agreed upon by all.”

By the 1900s, birthing became medicalized. University-trained midwives — often males — and obstetricians viewed pregnancy as a condition that needed treatment. After the U.S. introduced a law that only doctors with licenses could deliver babies, midwives that lacked formal training in medicine were eroded from the narrative of births.

“There was a big shift in what we considered a safe and an appropriate place to birth,” says Winick. “While the central tenet of midwifery practice was to meet women where they are, the controlled environment of a hospital meant access to the vagina for a doctor’s convenience.”

The road less taken

In the process, women have become saddled with health risks to which they might be oblivious. Compared with lying down, birthing upright has advantages such as wider pelvic space, less physical trauma, effective contractions, reduced labor pain, and higher satisfaction.

When the mother is recumbent, the baby’s health may also take a hit. Lying back can lower maternal blood pressure and, thus, blood flow to the fetus, as such a position compresses major blood vessels in the mother’s uterus. Keeping mothers upright allows them to be more mobile, compared with being in repose, which reduces the risks of fetal heart rate abnormalities.

The physical forces to push the baby out of the vagina upright and horizontal positions differ greatly. In upright positions, the birthing process gets some help from gravity. Women may spend about an hour and half less if they give birth in upright positions as compared with doing so horizontally, because the uterus contracts more efficiently when the woman is vertical. On top of shorter deliveries, women have reported less pain on average in sitting birth positions as compared with lying back.

When women are horizontal, doctors can monitor their blood pressures and the heart rates of their babies more easily. Back birthing also provides doctors more access to administer trauma-prevention procedures such as vaginal massages to the mother. But delivering while lying back carries a risk of major tears. It heightens the need for doctors to perform emergency surgeries to more than double that of upright birthing positions. Women giving birth in a kneeling position are 94% less likely to suffer severe tears than mothers giving birth lying back.

“[Birthing on the back] became the most popular reason because of the ease of the person delivering the baby rather than the comfort of the mom,” says Deborah Sherman, an obstetrician for Ob Hospitalist Group.

During natural births, women can suffer from a series of negative mental health outcomes when they perceive a lack of agency in their own birthing process, including the power to choose their birthing position. Studies show that women can find it hard to connect with their baby and even avoid pregnancy in the future if they had a distressing childbirth.

Standing up for change

Providers need to make a range of birthing positions available to women, starting with empowering women with that knowledge. “We need to do a better job at understanding the preferences of individuals who are planning for a vaginal birth,” says Allison Bryant Mantha, an obstetrician/gynecologist and maternal-fetal medicine specialist at Massachusetts General Hospital. “We should keep checking in over the course of labor to make sure that we can meet those preferences safely. This approach absolutely leads to a better birth experience for individuals and their families.”

Women giving birth in a kneeling position are 94% less likely to suffer severe tears than mothers giving birth lying back.

Picking a single “best” position for everyone is tricky, not to mention dangerous. It’s impossible to conduct clinical trials for examining the nuances of the ‘ideal’ birthing position, because individually assigning pregnant women one birthing position or another is unethical. But when women are free to adopt various birthing positions, researchers will also be better able to collect real-world data about upright positions and improve guidelines.

To get here, Sherman says that doctors and nurses need to be educated on which birthing positions are better for which kind of patient and for what purposes. Only then can they educate mothers to make informed decisions regarding birthing positions.

Hospitals also need to diversify their spaces with birthing chairs, bean bags, mats, and poles. A study published in the journal Women and Birth shows that when these paraphernalia are available, women go for upright or forward leaning positions three times more often than when they give birth in a hospital devoid of these tools.

Many birthing women opt for epidurals, a numbing, mobility-reducing agent that mothers might take for labor pain. And epidurals are compatible with women lying back, kneeling or the use of birthing stools.

Historical western standards influenced many countries to keep pregnant women on their backs, even in places where upright positions were once overwhelmingly preferred for childbirth. Nevertheless, a shift in medical guidance is underway in countries that the U.S. can look toward. In Germany and the U.K., national guidelines recommend doctors to promote alternative labor positions and avoid advocating for mothers to lie back. The key here is for women to adopt any position that they find the most comfortable. It’s time for the rest of the world to follow suit and empower birthing women to decide their own pregnancy journey for themselves, a basic step for improving overall health outcomes for mother and baby.