This essay was produced through Sequencer's Storytelling Mentorship Program. Your support through donations and subscriptions helps early-career scientists and creatives tell stories you won't find elsewhere.

If you can spare a few bucks, consider enabling us to continue this work with a one-time donation or regular subscription for as little as $0. Thank you.

Humans come with a few standard abilities built in. They’re good at moving from place to place under their own power, surviving infections, doing manual labor, and foraging for food.

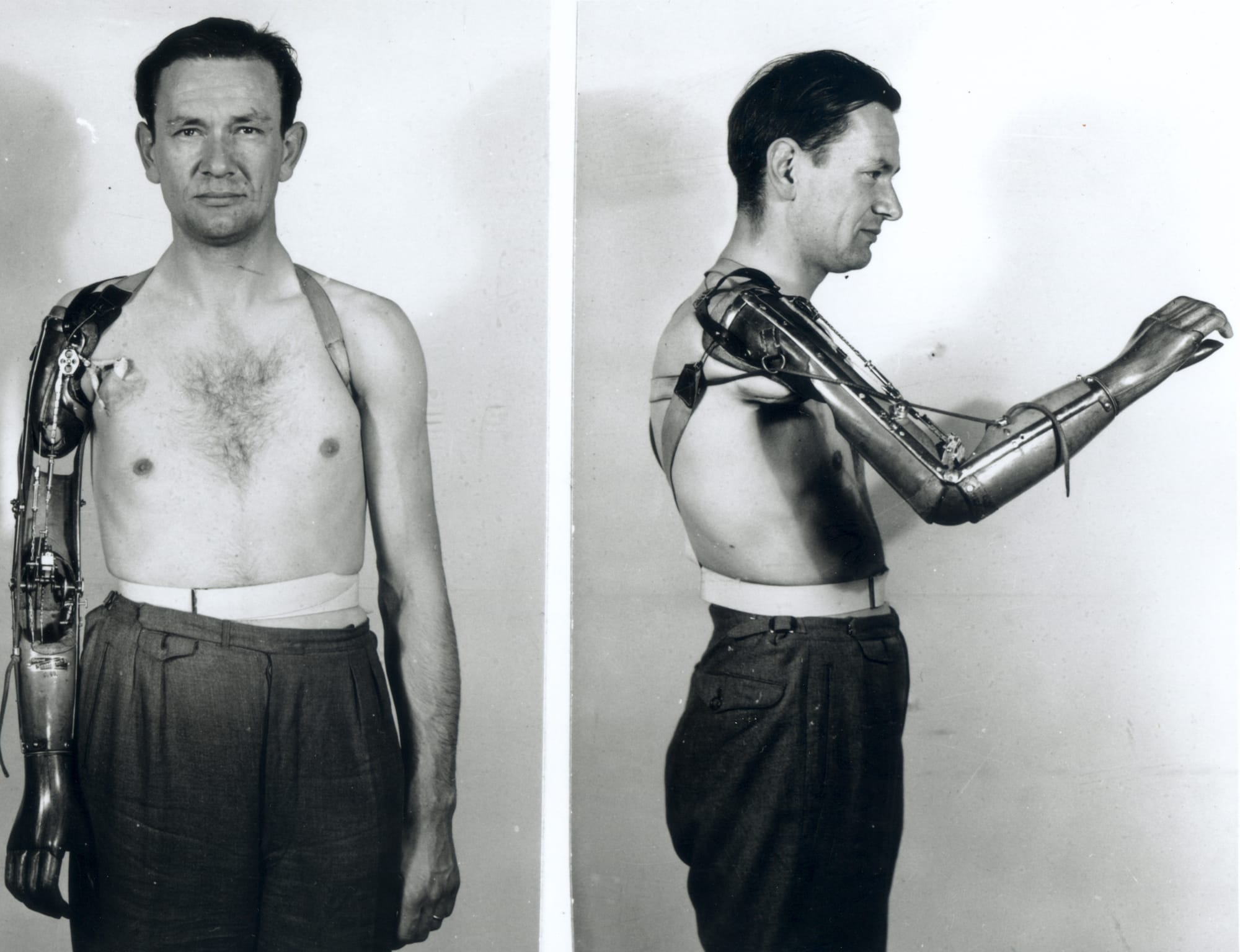

To go beyond that, humans augment themselves in order to improve performance. The history of augmentations includes the use of agriculture over foraging, printing over handwriting, machines powered by steam and gasoline over manual labor, and the radio and the internet over just yelling.

Now, humanity is again on the cusp of a new frontier: cyborgization— evolution that transcends biology.

UC Santa Cruz lecturer Chris Hables Gray wrote in his book Cyborg Citizen that a cyborg is “any organism/system that mixes the evolved and the made, the living and the inanimate,” a definition so broad that it even includes anyone who has received a vaccination. Transhumanists sometimes idealize cyborgization, viewing it as a liberation movement, “a total emancipation from biology itself.”

Unfortunately, the law is not up to date with dealing with this new class of human. In fact, the language is not even current. A less politicized term, “hybrid human,” started gaining traction in 2022 when author, veteran, and double amputee Harry Parker wrote that terms like cyborg “conjure too many fictions and unrealistic expectations.”

Simply put, when the law fails to keep pace with technology, consumers are left unprotected. In a world ruled by profit, life-sustaining medical devices are just as commodified as anything else. These products can be abandoned inside patients, forcibly removed from them, shut off without warning, or implanted despite known risks of failure. If making the safe, ethical move seems too costly for manufacturers, there is little the user can do to fight back.

Cyborgs urgently need better rights over their devices, which in some senses are indistinguishable from their bodies. If cyborgs are a class of human, they require recognition under the law, in the same way that the Americans with Disabilities Act protects people with disabilities, and Title IX protects women and LGBTQIA+ people. They need a legal basis for personal injury claims when businesses prioritize cost cutting over treating life-sustaining devices. Disturbingly, cyborg bodily injuries are usually classified as mere property damage.