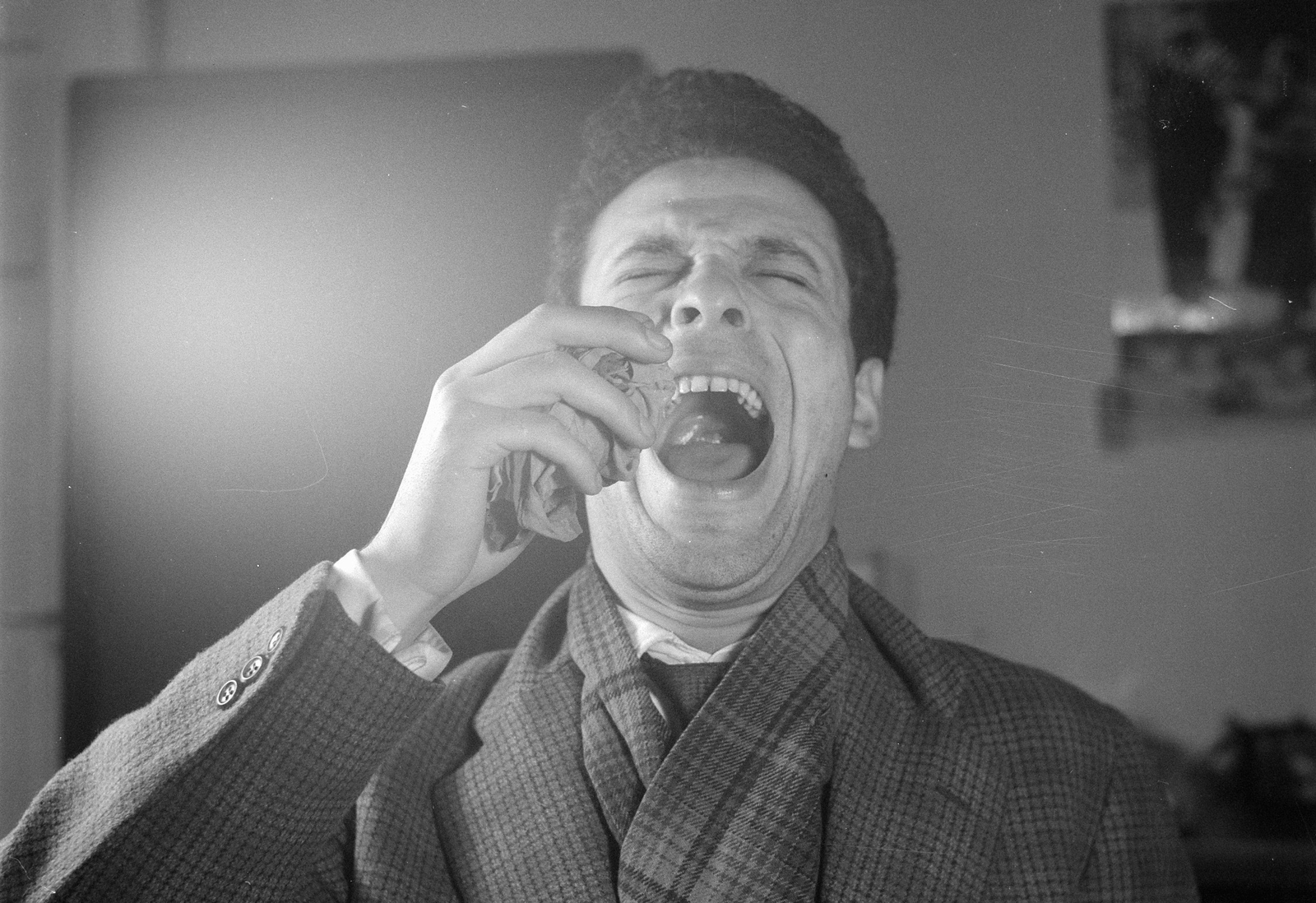

For a few years, we briefly lived through the golden age of studying what lives in the air, how it travels around, and how it might spread infections to humans, plants, and animals. But this critical area of scientific inquiry is nothing new. In his new book Air-Borne: The Hidden History of the Life We Breathe, New York Times science reporter Carl Zimmer writes about a lost history of mistakes and misconceptions, and the reinvigoration of aerobiology that 21st-century epidemics helped bring about. I reached Zimmer by phone at his Connecticut home, while he prepared a slideshow for an upcoming talk on his book tour.

This conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

How did this book come about? “The biology of the air” seems like one of the most pertinent topics in science right now, it seems strange that this is the first popsci book on the topic.

Well, the seed for the book was planted during the pandemic. I was trying to report on the science of COVID, along with a lot of other science writers. This was a disease scientists were trying to figure out in real time.

It was a challenging job, people were learning about it really on the fly. What seemed to be initially true turned out not to be true. One thing that struck me was how much an argument there was about how [COVID] spread.

Naively, it didn’t seem like it should be so complicated. I got to understand the nature of the arguments and conflict by talking with people. People kept pointing me back to before the pandemic. There were these conflicts that were going on for a long time.

The more I went back, the more I realized that these issues about the air go back much longer than just COVID. They’ve been quite neglected, and there have been all of these remarkable people who I’d never heard of before, who’d had no biographies written about them, who were just lost.

What were those conflicts?

The biggest conflict about the air is how it can make you sick. For centuries, there was a widespread belief that the air itself could become corrupt and would carry in it miasmas. If you breathed in these miasmas you disturbed the humors of your body and you became sick with all these diseases—like malaria. The disease is in the name, mal air.

Microbiologists began to say no, no, there’s no miasma, it’s just bacteria being spread in the water, food, through sex, maybe a cough at short range, but the air is harmless. The idea of airborne infection disappeared by the end of the 19th century.

I also want to remind people that if you breathe in a coronavirus, you might well get COVID, but the fact is with every breath you take you’re inhaling living things. They’re regular visitors to our airways. The really remarkable thing is that we’re not getting sick all the time

In the 1930s, William and Mildred Wells, a husband and wife team, along with other scientists showed that air can carry infections over long distances. They were promptly thrown into oblivion.*

When COVID came roaring back, a lot of people had to rediscover the Wells, people had to reacquaint themselves with that old work.